Exploring the Health Impacts of Air Quality from Drought

Krishna Kolen is working with Mistawasis Nêhiyawak to learn more about how air quality due to drought affects the health of community members.

A research idea first sparked out of concern from Mistawasis community members in 2022 has grown into a multi-year collaboration bridging climate science, public health, and community partnership. During her master’s program, Krishna investigated how dry conditions can degrade air quality and heighten health risks across Saskatchewan. That work not only revealed how quickly drought impacts can escalate, but also laid the groundwork for her PhD, which brings these questions into sharper focus at the community scale.

Now a PhD candidate in the Department of Geography and Planning at the University of Saskatchewan with Dr. Corinne Schuster-Wallace and Dr. Krystopher Chutko, and CIHR Vanier Scholar, Krishna’s doctoral project is being developed in partnership with Mistawasis Nêhiyawak, a First Nations community in central Saskatchewan that is seeing firsthand the impacts of changing climate and increasingly variable air quality. Krishna and the Mistawasis Lands and Health departments have partnered to understand how drought-related air quality is affecting the wellbeing of Mistawasis community members. Together, they are combining Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being with Western science to explore what tools, strategies, or monitoring approaches can help to better understand and reduce those impacts.

We connected with Krishna, who also leads the GIWS Students and Young Researchers, to learn more about her research and her partnership with Mistawasis.

1. In your master’s project, what did you discover about how events like dust storms and wildfires are affecting air quality and health across Saskatchewan?

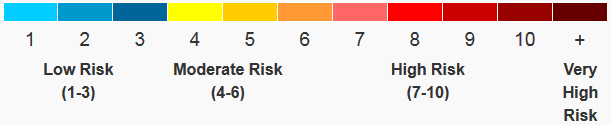

In my master’s project, I used provincial health data from each health region and looked to see if there were increases in risk of hospitalization during air quality events that were at an Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) of 7 or above (the level where risk to health becomes high) between 2015 and 2022.

Air Quality Health Index (AQHI)

(Source: https://weather.gc.ca)

My research found that from 2015-2022, when there were air quality events caused by dust storms and wildfire smoke of 7 and above, there was increased risk of hospitalizations for cardiovascular, respiratory, and stress and mental health-related impacts across Saskatchewan health regions. These health risks varied across health regions and for males and females. This occurred for both females and males in multiple, but not always the same, health regions. We were not able to look at other identifying information (age, where people live, gender, etc.) to ensure privacy, which pointed us towards the need for more localized and community-based research.

2. What aspects of your master’s research pointed you toward the need for more localized, community-based research?

The work that I did in my Master’s was on the scale of health regions and air zones, so I was able to see that there was an increased risk to health during these air quality events, but not who was most at risk (for example, potential risk factors such as age, gender, where people live). Research has shown that people who have pre-existing health conditions and those who live in rural and remote communities are more likely to be impacted. It also shows that Indigenous communities are likely to be more at risk because of the impacts of colonialism, including through the loss of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, exclusion in decision making related to climate adaptation and health, and a legacy of poor housing. This is something that we are unable to see at a health region scale, so we need to work collaboratively with those communities to co-create adaptation strategies that are relevant to specific communities and to protect against the impacts of air quality.

3. How did you begin working with Mistawasis, and what motivated the community to explore the local health impacts of drought-related air quality?

My co-supervisor, Dr. Corinne Schuster-Wallace, introduced me to Mistawasis as an undergrad student through a course (GEOG 465) that is held in partnership with Mistawasis’ high school and the Department of Geography and Planning. In this course, I had the opportunity to stay in Mistawasis for one week and learn together with the high school science class, Elders, and my university classmates about the community and ways that we can connect Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being with Western science.

During this trip, Corinne and I had the opportunity to connect with Anthony Blair Dreaver Johnston (an Elder and Special Projects Advisor from Mistawasis) and the Health Center Director, Beverly Wise, where we had some conversations about how there is concern about how air quality was impacting community members’ health. These conversations allowed us to work collaboratively on a smaller project in 2024 that asked community members to self-report how air quality impacts their health. We also spoke to staff members at the health center, members of leadership, and Knowledge Holders and Elders to learn more about how air quality is impacting the community on a wider scale, which raised several questions and concerns, including what air quality is, how it impacts the community, and how the community can adapt. This smaller project prompted a desire from the community to continue this collaborative work to better understand who in the community is impacted, how people are impacted, to raise awareness about air quality and its impacts in the community, and to use this information to inform future community responses to reduce exposure to and the impacts of air quality in the community.

4. How are you and the community working together to identify the conditions that most impact local health?

We are doing this in a number of ways:

- Youth research associates from the community will facilitate the research process with me, including participant recruitment, data collection, analysis, and sharing of results.

- The Mistawasis Lands Department will support creating a low-cost sensor network indoors and outdoors of public buildings and homes of volunteer community members to monitor local air quality changes. Community members can also volunteer to wear portable sensors to understand how day-to-day activities might impact exposure to air quality.

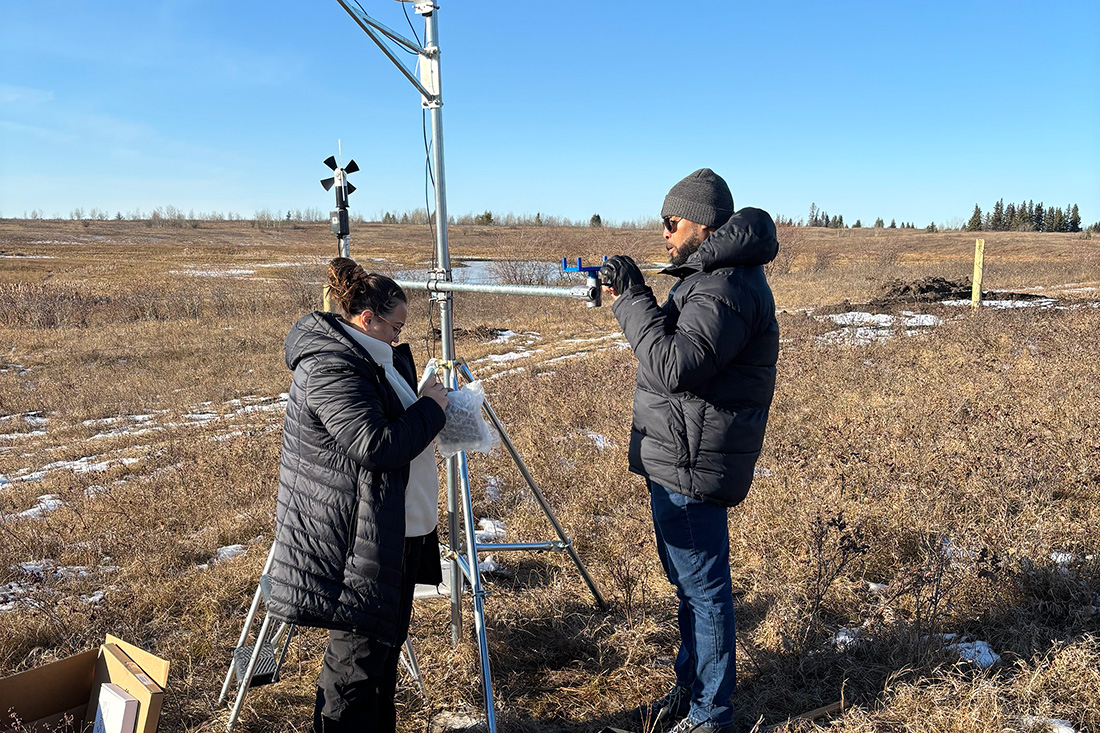

- In addition, the Mistawasis Lands Department will support collecting weather data using a pre-existing weather station on the north side of the community (part of a network of stations in First Nations communities across Saskatchewan from a project led by Dr. Krystopher Chutko and Dr. Robert Patrick) and a new weather station we installed on the south side of the community. The combination of the weather data from both stations will be used to better understand what weather conditions look like before and during air quality events.

- We’ll closely collaborate with the Health Center to better understand local disease burden and impacts of air quality on health through surveys and analysis of health intakes at the health center during air quality caused by dust and smoke.

- Interviews and sharing circles that specifically involve leadership, youth, Traditional Knowledge Holders and Elders, and representatives from different groups within the community will help understand what challenges the community faces related to air quality, what is currently being done to mitigate and adapt to air quality events, and what potential solutions there are to adapt to air quality events.

- The results will be co-analyzed with the community, ensuring that the community members provide their input and can be used by Mistawasis leadership to inform context- and community-specific governance strategies to adapt to air quality events.

5. Looking ahead, what tools or approaches are you hoping to co-develop with Mistawasis to better understand and mitigate the health impacts of drought-induced air quality?

At this point, I am not sure what we will come up with together. I think that is the beauty of community-based participatory research – we work and learn together to develop strategies that are relevant and useful to the community for climate adaptation. This is something that we will come up with as we go by braiding Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and Western science. Braiding these knowledge systems allows us to bring together multiple types of knowledge by complementing, supporting, and enriching one another through a process of mutual respect, reciprocity, trust, and cooperation. This process of learning together will allow us to co-create strategies with data that are owned by the community and contributes to Indigenous data sovereignty, climate adaptation, and resilience.