Balancing Act

This article first appeared in the Fall 2014 edition of the U of S alumni magazine The Green and White

By Derrick Kunz

This article first appeared in the Fall 2014 edition of the U of S alumni magazine The Green and White.

Markus Hecker paints contrasting views of water he experienced as a young boy. One was watching Jacques Cousteau explore the unchartered depths of the ocean—an underwater world yet unseen by human eyes. The other of the Elbe and Rhine rivers being so polluted from Cold War-era industrialization that they were unsafe for residents to touch.

The latter abruptly interrupted the mystical images of the former with the harsh reality that our water is very susceptible to human abuses. Both piqued Hecker’s curiosity to understand the delicate balance between using water for our benefit and reducing impact on the environment and ecosystems.

Now a Canada Research Chair with joint appointments at the U of S School of Environment and Sustainability and the Toxicology Centre, Hecker is studying what human society is releasing into water and its impact on the aquatic ecosystem and human health. “In the 1980s and 90s we obtained a pretty good understanding of the risks posed by metals and certain industrial chemicals in water and how to deal with them,” said Hecker. “But there is an ever increasing number of so-called emerging contaminants that we have very limited or no information on with regard to their toxic properties, and we need to better understand what their impact is on the quality of water for animals and humans.

“For a municipal water treatment plant, there’s a potpourri: pharmaceuticals, personal care products, hormones like estrogens from birth control pills, BPA from water bottles and plastic containers—most of that ends up in our wastewater,” explained Hecker. “Treatment plants, even really sophisticated ones, aren’t designed to take most of these chemicals out.”

We do not understand the extent or ramifications of pollution in our Canadian waterways yet, but Hecker used the feminization of male fish from elevated estrogen levels in some European waterways as a precautionary example. “In some streams we are seeing massive feminization, or demasculinization, of male fish downstream of wastewater treatment plants. What effect does that have on the fish populations?” Or on the entire ecosystem? Or people who drink the water and eat the fish?

Hecker’s research seeks to find out which of the tens-of-thousands of chemicals that are currently in use end up in our water, at what concentration they are present, which ones are harmful or beneficial, if they naturally break down and at what rate, and what they do to the ecosystem and human health.

“We need to better understand the risks and balance them against what is safe,” said Hecker, highlighting the fact that eliminating all chemicals in modern society is not feasible.

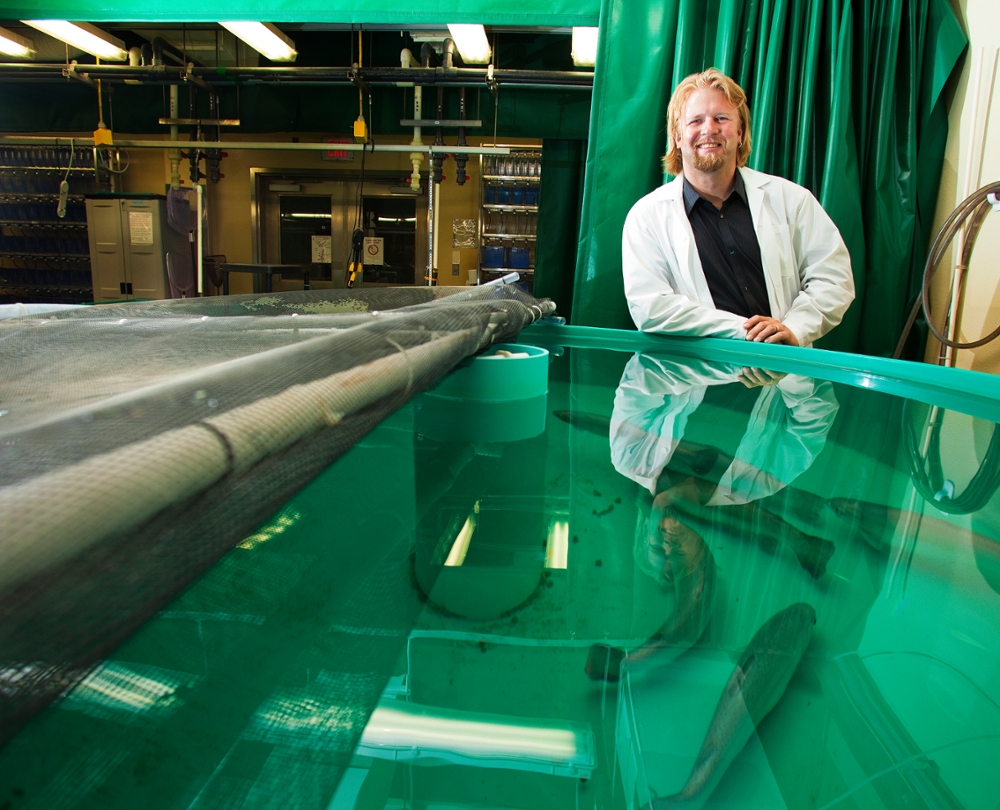

The U of S Aquatic Toxicology Research Facility—the only one of its kind in Canada— helps Hecker gain that much needed understanding. The self-sufficient facility can house almost any type of fish, including endangered and native species like sturgeon, pike and whitefish, and allows researchers to control experimental water conditions—such as temperature, pH levels and concentration of various chemicals—to solve real-world problems.

Hecker said that we still have a lot to learn in understanding and mitigating risks to our water. As an academic researcher, he is in a position to work with both industry and government to find the balance between progress and policy. And he is training the next generation of researchers who will continue to make a difference.

“We derive great benefits from chemistry, but we have to take care to not negatively impact wildlife and people. There is still a lot that we don’t know.”

Like Cousteau, Hecker is exploring unchartered territory to help us understand, and be good stewards of, our water.